by Airbus CyberSecurity’s Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) Team

As a result of the recent SolarWinds[1] campaign, supply-chain compromises are getting more visibility. This technique consists of “manipulating a product prior to receipt by the final user to compromise the system or data”[2]. The affected product can be compromised by prior modification of the hardware, the software or its dependencies or development tools.

Like phishing e-mails they aim to provide a foothold on the system for an attacker. But, unlike phishing, of which people are becoming more aware, supply-chain compromises are more difficult to detect at first glance. They impersonate a legitimate hardware, software or update from a reliable source (supplier, manufacturer, trustworthy application market etc.). Some sophisticated malicious actors target trusted editors to modify its product source code, achieving a supply-chain compromise. This allows them to obtain an affected product signed by the editor’s certificate, making it undetectable before first use.

Supply-chain compromises also differentiate themselves from phishing with a wider range of potential system to corrupt. They can go from Industrial Control Systems (ICS), to dedicated administration platforms and other critical systems, whereas a malware delivered through phishing would be confined to a platform with an email client before having to pivot on to the target system.

Threat Actors

As they do not need prior social-engineering actions like phishing e-mails or do not exploit human faults like typosquatting, supply-chain compromises are regularly used as a technique to get a first foothold on a target’s network.

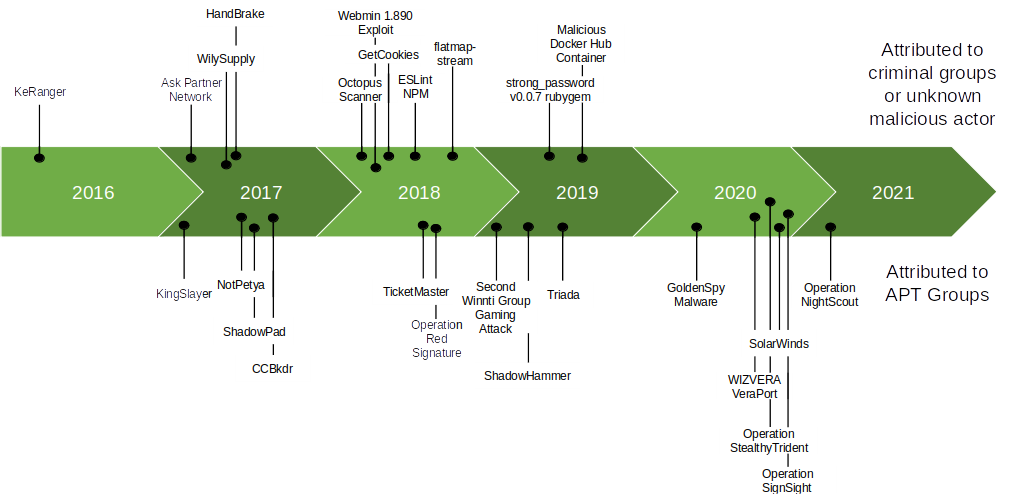

Figure 1 : Attacks using a supply-chain compromise (not exhaustive)

Typically, criminal groups are looking to profit from their actions by aiming to deliver the compromised product to a maximum number of targets. This could be done by targeting docker containers[3] or popular open source repositories[4]. Once the corrupted product is deployed it would deliver its payload, such as an adware, crypto-miner, ransomware or information-stealer.

Close to criminal actors, other malicious actors might aim to corrupt some known repositories to insert backdoors or further exploits in future products developed within those environments.

Another type of threat actor, Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups would aim for either intelligence gathering (SolarWinds) or to assert their dominance in the field of cyberwarfare (NotPetya[5]). What generally differentiates them from cybercrime actors is the targeting of the victim. The tactics used would be to corrupt the maximum number of devices, then lay dormant if the victim is not among the initial targets, or deliver a second stage payload if the victim is among the target list (CCBkdr[6, 7]). A first filter can be done by choosing a product mainly used by their targeted victims (Operation NightScout[8]), hence it is possible a user could have a compromised product that has never been exploited because they were not among the target list of the attackers. More direct approaches by APT groups have also been observed, where they have been able to gain access to offline or isolated systems and have then been able to operate within that environment with the clearances provided by the compromised product.

What sets the SolarWinds campaign apart from other APT groups campaigns that relied on supply-chain compromise, are the numerous tricks used to hide the fact that the product update was backdoored. Among these tricks, the compromised update is able to detect if forensic tools are deployed on the targeted system and if an anti-virus is running. Once installed, the backdoor lays dormant for several days before acting. Then, it masquerades its network activity as the corrupted process to further hide itself.

Mitigation

Supply-chain compromises use tactics to blend themselves into the corrupted environment and are delivered by trusted sources. This turns a legitimate process into an illegitimate one, making supply-chain compromises hard to detect on the first run.

But nonetheless, some mitigation processes can be applied:

Having an improved Software Installation and Update policy can help to detect supply-chain compromises before integrating them in a running environment. Performing a static analysis on new products or updates, if the regulation allows it, enables the monitoring of changes between two versions and/or watch for hidden backdoors. A dynamic analysis in a sandboxed environment can further complete a first audit to watch out for unusual activity. Finding a compromise in the supply-chain requires having understanding of how the compromise works in the infected product and how it was established there. To this end, cooperation with the supplier of the product is necessary, even more so in the case of an established compromise.

However, performing this type of verification is rare and expensive. These are practices that are not implemented in IT security policies. Off-the-shelf products are considered safe, which does not encourage companies to take this type of action before IT deployments.To further asses the trustworthiness of a supplier, an audit of the products and of the supplier process can be entrusted to a red team. In any case, even if prior analyses were performed, the system process and network communications should be continuously monitored to ensure the ongoing security of your systems.

Conclusion

Supply-chain compromises abuse trust in legitimate products. They allow rebound infection through an editor and spread it by allowing a large number of targets to be hit without additional significant compromise effort. Preventing this type of attack is complicated and expensive as well as detecting it. Quite often the communications of supposedly legitimate software are whitelisted on firewalls and are not thoroughly verified by analysts. For this reason, it can be important to have a dedicated process for checking these applications. IT and security teams could check the flows, and monitor the tools processes to see if they perform strange actions such as process execution, file writing, network communications to other IT machines, etc.

It is important to note that this type of attack has been coming back regularly for a few years and has significant impacts. It is also very important that publishers increase their level of security to protect their customers from this type of infection but also to avoid a loss in credibility and reputation. However, publishers must be reactive in the same way as when patching vulnerabilities when this type of attack is detected. They must inform their communities or customers to allow them to develop an adequate understanding of the attack and an efficient remediation to it.

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) Team

Airbus CyberSecurity’s CTI Team help you to protect yourself against the latest threats with our constant Cyber Threat Intelligence monitoring.

We help governments, military, Airbus and critical national infrastructure with their cyber protection.

Our team, located in France, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom, bring together experts who work daily to monitor the security status of digital environments in real time and provide our advanced cyber security services.

Our threat intelligence benefits from the know-how and experience of our SOCs (Security Operations Centre) and CSIRT (Computer Security Incident Response Team) teams.

References

[1] FireEye: Highly Evasive Attacker Leverages SolarWinds Supply Chain to Compromise Multiple Global Victims With SUNBURST Backdoor, December 13, 2020.

[2] MITRE ATT&CK, T1195: Supply Chain Compromise.

[3] Trend Micro: Malicious Docker Hub Container Images Used for Cryptocurrency Mining, August 19, 2020.

[4] Bleeping Computer: Malicious Python Package Available in PyPI Repo for a Year, December 4, 2019.

[5] Bleeping Computer: Petya Ransomware Outbreak Originated in Ukraine via Tainted Accounting Software, June 27, 2017.

[6] Avast: Progress on CCleaner Investigation, September 10, 2017.

[7] Cisco Talos: CCleanup: A Vast Number of Machines at Risk, September 18, 2017.

[8] ESET: Operation NightScout: Supply chain attack targets online gaming in Asia, February 1, 2021.